Liberty cap: the surprising tale of how UK and Europe’s magic mushroom got its name

It’s autumn, the best season for mushroom pickers. And mushrooms – specifically magic ones – are in the spotlight. A growing body of research is showing that psilocybin, the main psychoactive compound in magic mushrooms, has potential in treating psychological disorders like depression, addiction and PTSD. The state of Oregon just voted to legalise the mushrooms for therapeutic use – a US first.

Of the nearly 200 species of psychedelic mushrooms that have been identified worldwide, only one – Psilocybe semilanceata – grows in any abundance in northern Europe. Like many mushrooms, Psilocybe semilanceata is generally known not by its scientific designation, but by its common or folk name, the “liberty cap” mushroom.

For years, this bothered me. As a Roman historian, I know the liberty cap (the pileus, in Latin) as a hat given to a Roman slave on the occasion of their being freed. It was a conical felt cap, shaped like that of a smurf, and which undeniably bears a clear resemblance to Psilocybe semilanceata’s distinctive pointy cap.

But how on earth did an obscure Roman social practice end up lending its name to a modern psychedelic? As I soon discovered, the answer takes us through an assassination, a number of revolutions, a bit of poetry, a dash of xenophobia, and a very unusual scientific discovery.

BUY MUSHROOM CHOCOLATES IN THE UK

Get your news from people who know what they’re talking about

The original liberty cap was an actual hat, worn by freed slaves in the Roman world to mark their status: no longer property, but never truly “free”, tainted by their history. For the freedman, it was a symbol both of pride and shame.

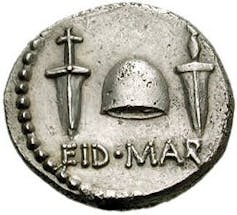

But in the year 44 BC, the hat gained a new cultural currency after Julius Caesar was famously murdered on the Ides of March (March 15). To advertise his part in the deed, Marcus Junius Brutus (of “et tu, Brute” fame) minted coins, the obverse of which bore the legend EID MAR beneath a pair of daggers and the distinctive liberty cap. Brutus’s meaning was clear: Rome herself had been freed from Caesar’s tyranny.

Brutus’s use of this symbol translated it from a low status social marker into an elite political symbol, and one that enjoyed a considerably longer life than the short-lived Brutus himself. Throughout the remainder of the Roman period the goddess Libertas and the liberty cap were a commonly employed shorthand by emperors keen to stress the freedom that their absolute rule bought.

Caps of revolution

With the collapse of Roman power in Europe in the fifth century AD, the liberty cap was forgotten. But then, during the 16th century, as interest in and explicit emulation of Roman antiquity began to spread through the countries of Europe, the liberty cap again reached public consciousness.

Books like Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia(1593) described the hat and its symbolism for educated audiences, and it again began to be used as a political symbol. When the Dutch drove the Spanish from Holland in 1577, coins bearing the liberty cap were minted, and William of Orange likewise minted liberty cap coins to commemorate his bloodless seizure of the English throne in 1688.

But it was in two of the great republican revolutions of the 18th century – the French and American revolutions – that it became a truly popular icon. Now blended with the visual form of the ancient Phrygian cap, the liberty cap (bonnet rougue in French) appeared no longer merely as a representational device but as an actual item of headwear or decoration.

In France, on June 20 1790, an armed mob stormed the royal apartments in the Tuileries and forced Louis XVI (later to be executed by the revolutionaries) to don the liberty cap. In America, revolutionary groups declared their rebellion against British rule by raising a liberty cap upon a pole in the public squares of their towns. In 1781 a medal, designed by no less than Benjamin Franklin to commemorate the fifth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, Libertas Americana (the personification of American Liberty) is depicted with wild, free flowing hair, the pole and cap of liberty slung across her shoulder.

From headwear to fungi

The revolutions of France and America were viewed with considerable disquiet from Britain. But the pole and cap of liberty clearly made an impact on a young poet by the name of James Woodhouse, whose 1803 poem, “Autumn and the Redbreast, an Ode”, paid a striking tribute to the varied beauty of mushrooms:

Whose tapering stems, robust, or light,

Like columns catch the searching sight,

To claim remark where e’er I roam;

Supporting each a shapely dome;

Like fair umbrellas, furl’d, or spread,

Display their many-colour’d head;

Grey, purple, yellow, white, or brown,

Shap’d like War’s shield, or Prelate’s crown—

Like Freedom’s cap, or Friar’s cowl,

Or China’s bright inverted bowl

This seems to be the first ever connection of the physical cap of liberty and the distinctive pixie cap of the mushroom. It was clearly not used because it was an established name (note his inventive imagery with the other shapes he describes), but rather coined by Woodhouse as a poetic flourish.

This metaphor caught the attention of a famous reader, Robert Southey, who had reviewed the volume in which the poem appeared in 1804. In 1812, Southey, along with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, published Omniana, a two volume collection of table talk and miscellaneous musings intended to educated and inform the would-be conversationalist. Nestled in among attacks upon Catholic traditions and notes upon early English metre was the following observation on the “Cap of Liberty”:

There is a common fungus, which so exactly represents the pole and cap of liberty, that it seems offered by nature herself as the appropriate emblem of Gallic republicanism, — mushroom patriots, with a mushroom cap of liberty.

Neither Woodhouse nor Southey and Coleridge identified the precise mushroom they had in mind with the cap of liberty metaphor. But as the discipline of mycology – the study of fungi – began to cement itself in the 19th century, a field driven by precisely the kind of gentleman scholars that would have kept a copy of Omniana on their shelves, the name was clearly and universally associated with Psilocybe semilanceata.

At that time, this was an utterly obscure and unremarkable little mushroom below the notice of any but devoted mycologists. As common names for mushrooms began to be included in mycological handbooks, Psilocybe semilanceata was routinely identified as the liberty cap.

Perhaps the earliest such example was in Mordecai Cooke’s 1871 Handbook of British Fungi. In 1894, Cooke published his Edible and Poisonous Mushrooms, which tellingly referred to Psilocybe semilanceata, within quotation marks, as “cap of liberty”, exactly the phrasing used by Coleridge, whom it would appear that Cooke was consciously quoting. By the 20th century, the name was firmly established.

A mushroom becomes magic

The story could, perhaps, end there, but it has a delightful coda, in which the liberty cap mushroom was propelled from total obscurity as merely one of literally hundreds of innocuous LBMs (little brown mushrooms) known only by scientific specialists to perhaps one of the best known members of Europe’s mycological fauna.

Throughout the literature written by Europeans on the customs and religions of the peoples of Central America, there existed rumours of a magical food that the Aztecs called teonanácatl (“the divine mushroom”). These rumours had long been discounted as superstitious mythologising, no more deserving of serious consideration than the shapeshifters of Norse and Icelandic saga. But in the early part of the 20th century, the divine mushroom captured the imagination of seemingly the most unlikely man on the planet, Robert Gordon Wasson, the vice president of the Wall Street banking firm JP Morgan.

Since the 1920s, Wasson had been obsessed with ethnomycology (the study of human cultural interactions with mushrooms). In the course of research that would lead to a voluminous bibliography, Wasson travelled to Mexico and there, after a long and frustrating search, finally found a woman who was willing to initiate him in the secrets of the sacred mushroom. He became (perhaps) the first white man to intentionally ingest a hallucinogenic fungus and published his experience in a 1957 Life article, “Seeking the Magic Mushroom”.

Wasson’s discovery was a sensation. In 1958 a team led by the Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann – the man who first synthesised (and ingested) LSD – was able to isolate the main psychoactive compound in the mushrooms, which was named psilocybin as a nod to the fact that it was primarily mushrooms of the genus Psilocybe that possessed the chemical. Though species of the hallucinogen fungi were most concentrated in Central America, they began to be found worldwide. In 1969, an article in Transactions of the British Mycological Society established that none other than the innocuous little liberty cap contained psilocybin.

Though there are other psychedelic species that grow in Britain (including the distinctive red and white Amanita muscaria – fly agaric – which contains muscimol not psilocybin), the liberty cap has secured a reputation as the poster-child for Britain’s domestically growing psychedelic fungi. Modern “shroomers” can’t resist punning on the liberty cap name – with its associations to the transcendental “liberation” afforded by psychedelics – and grassroots organisations such as the Shroom Liberation Front attest to this fact.

But in origin, the liberty cap’s name has nothing to do with psychologist and psychedelic drug advocate Timothy Leary (“turn on, tune in, drop out”) or the 1960s counter culture. Rather – and somewhat improbably – it traces a path back through the political revolutions of the early modern period, via the murder of the tyrant Julius Caesar, to a conical cap worn by Rome’s former slaves.

How to Identify Liberty Cap Mushrooms

The dainty, ribbed and pointed cap on slender stems belie a potentially poisonous little edible growing in grasslands around the world. The Liberty Cap mushroom, also known as a magic mushroom for its psychedelic effects, has long been used as a hallucinogenic in many cultures around the world for thousands of years. While some say it is safer to ingest than processed drugs for a fast feeling of euphoria that can last for hours, the Liberty Cap mushroom can also be dangerous to ingest.

Liberty Cap Mushroom Facts

- The Liberty Cap mushroom is also known as a magic mushroom. The flesh of Liberty Cap mushrooms contains the psychoactive compounds of psilocybin.There are nearly 200 varieties of psilocybin mushrooms growing in damp, grassy areas all over the world.It is wildly abundant in forests and glens. It is also one of the most potent types of mushrooms found on the floors of wooded areas and in grassy knolls.The Liberty Cap mushroom is a dainty and potentially deadly mushroom. The pointy-capped plant has its benefits and its risks.

The Liberty Cap has a long growing season, continually sprouting from August to November.

Shape of Liberty Cap Mushrooms

While the different types of edible mushrooms that are stuffed on grocery shelves can be confusing to identify, Liberty Cap mushrooms have a distinct shape that can alert mushroom pickers.

Liberty Cap mushrooms are so called because of the distinctive hat they wear on their weaving stalks. The bell-shaped, conical caps are barely an inch in diameter. The caps come to a pointy head and are chartreuse to brown in coloring. They have long lines that radiate down the moist caps. As they mature, the color fades from a rich taupe to a grayish brown.

The grooves that run from the nipple-like top down to the rounded-edged bottom tend to fade as the mushroom dries out. This can make dried psilocybe semilanceata mushrooms harder to distinguish from their less-dangerous and passive counterparts.

Where Liberty Cap Mushrooms Grow

The tiny-capped mushrooms prefer wet areas that are undisturbed by foot traffic or grazing by farm animals. They can be found growing in thick numbers in grassland habitats. Liberty caps also like to grow in cooler areas like the Pacific Northwest of the United States, but they’re also becoming more common in the UK as temperatures increase over the cooler months. Normally it takes a freeze for the fungi to die off.

Identifying Magic Mushrooms

It can be rather difficult to identify mushrooms that you have picked from the wild. There are many different types of magic mushrooms aside from the Liberty Cap. To know if you are picking magic mushrooms when foraging for the spongy edibles, there are a few distinct things to look for.

- Search in the lower areas of meadows and fields.

- Liberty Caps are common on the west coast of the United States, particularly in the northwestern states of Washington and Oregon.

- If the cap leaves behind dark, purplish-brown spores when placed on a piece of paper while drying out, it is more than likely a Liberty Cap mushroom.

Dangers of Picking Wild Mushrooms

If you are not sure what a psychedelic-inducing mushroom looks like, then you probably shouldn’t traipse through the woods randomly picking mushrooms.

It can be hard to distinguish a nonpsilocybin mushroom from a magic mushroom that will alter your state of mind. The accidental ingestion of psilocybin mushrooms can create lasting psychological effects. Because they are natural, ingesting them can produce unpredictable results.

Types of Magic Mushrooms

There are dozens of species of psychedelic mushrooms that grow in fields and forests around the world. The average size of the magic mushroom species is tiny. They grow to just 3 inches with a 1-inch cap.

- Psilocybe semilanceata – This is the actual Liberty Cap mushroom. It adores a damp place to grow its delicate stems and caps. It doesn’t like dung but does like a wet, marshy ground with good, natural fertilizer. It can be mistaken for psilocybe pelliculosa, which can be a serious mistake. The psilocybe semilanceata is much stronger than its cousin psilocybe pelliculosa.

- Psilocybe baeocystis – Found growing in cheery groups along the tops of rotting logs, mounds of peat or mulch, this dark-brown capped mushroom also goes by the names of blue bell and bottle cap.

- Psilocybe cubensis – Larger than other varieties in this genus, this type of magic mushroom is the most common. It is also called a golden cap or Mexican mushroom. It can be identified by its reddish-brown cap over a pale yellow or white stem. The skin of this magic mushroom turns bluish when it is crushed while still fresh and sticky. It enjoys mounds of dung where it can proliferate.

Dangers of Magic Mushrooms

The United States Drug Enforcement Administration classifies psilocybin as a Schedule 1 controlled substance. This means the DEA views it as a dangerous drug that can be abused with no medical importance.

It can cause some problems such as:

- Irregular breathing

- Irregular heartbeat

- Potential psychotic states

- Potential seizures

- Increase in blood pressure

- Temporary vision problems

It is nearly impossible to truly gauge the exact amount of psilocybin you are ingesting when munching on dried magic mushrooms or sipping on Liberty Cap-infused teas.

History of Magic Mushrooms

Hallucinogenic mushrooms have been used in religious ceremonies and for medicinal purposes for more than 7,000 years. Mayan and Aztec cultures in Mesoamerica used the psilocybin mushrooms until Spanish conquerors forbade the use of them around the 15th century as a way to control the society’s culture.

What Is Psilocybin?

The psilocybin that is found in Liberty Cap mushrooms is a known hallucinogenic. It is created from the DNA of the mushroom as it blossoms from its moist foundation into a pointy-capped edible.

How to Eat Liberty Cap or Magic Mushrooms

Generally, any type of magic mushroom, including the Liberty Cap, is eaten after it has gone through a drying process. The mushrooms can be gritty or chalky when eaten whole and without any accompaniments.

The stems and caps of psilocybin mushrooms can also be gently boiled in a tea to be sipped. It has a strong, earthy scent and taste. Honey or sugar can be added to the tea without adversely affecting the potency of the mushrooms.

Magic mushrooms are often put on top of pizza, made into a chunky paste and spread on bread like a tapenade or baked into pasta dishes. This can lower the effect of the mushroom’s psychedelic properties. The more food you digest with the mushrooms, the more it will affect the way that the edibles are metabolized in your system.

Typical Magic Mushroom Dose

It can be hard to overdose on magic mushrooms. However, complications can arise when ingesting any natural ingredient that will affect your mindset and mood.

It takes .2 to .5 grams of dried magic mushrooms to begin to feel the effects of the psilocybin. Height, weight and metabolism affect how a person may feel when ingesting magic mushrooms.

For a lengthy psychedelic experience that can last between three and six hours, the average adult should take a moderate dose of 1 to 2.5 grams.